Cymdeithas Madog Chair Competition

- Details

- Written by: John Otley

- Category: Cymdeithas Madog Chair Competition

- Hits: 3320

History of the Cymdeithas Madog Chair

At each Cymdeithas Madog Cwrs Cymraeg since Cwrs Cymraeg Wisconsin in 1988, Cymdeithas Madog has held a competition in Welsh language literature composition among the students attending the cwrs. The topic and form (e.g., poetry, prose, etc) are announced before the cwrs in order to give participants in the upper levels time to compose their entries. The entries are of an extremely high standard. In order to preserve fairness, each competitor signs her/his entry with a "ffug enw" or "bardic name". The best entry each year that meets Cymdeithas Madog's high standards (as judged by the Cwrs tutors) is awarded the prized Cymdeithas Madog chair.

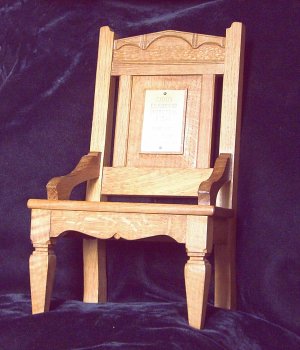

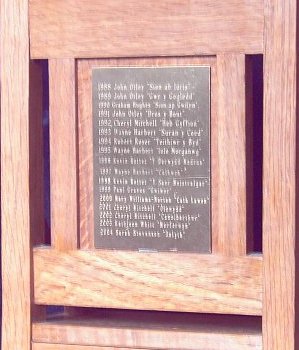

One of the most important and eagerly anticipated moments at every National Eisteddfod in Wales in the awarding of the chair to the winning bard in the strict meter competition. The chair is always crafted by a local artisan and reflects local tradition. The Cymdeithas Madog chair, commissioned by Mrs. Cassie Hughes of Bridgend, Wales, was carved by her brother, Huw Selwyn Owen. Mr. Owen, a master carver from North Wales (and a poet of distinction in his own right) was commissioned to make the official chair for the 1989 Llanrwst National Eisteddfod. The Cymdeithas Madog miniature chair was carved from the same wood, an oaken beam taken from a building dating from about 1400, as the Llanrwst National Eisteddfod chair. And like the Llanrwst chair, the back of the Cymdeithas Madog chair has a beautiful representation of the Llanrwst bridge.

Iif there is a worthy entry, this beautiful miniature chair is awarded to the winning bard in a formal chairing ceremony. The bard's name is engraved on a plaque on the back.

- Details

- Written by: John Otley

- Category: Cymdeithas Madog Chair Competition

- Hits: 2115

Y gerdd fuddugol yn nghystadleuaeth Gadair Cymdeithas Madog, Cwrs Cymraeg Wisconsin, 1988 gan Sion ab Idris (John Otley)

Delweddau Wrth Feddwl Am Y Ffin

Mi ddaeth fflam dros y ffin i newid ein byd.

Ond beth wyt ti'n gofio?

cornau a cheffylau?

concwerwyr a chestyll?

cyfreithiau a chadwyni?

Cofiwch y gogoniant drud.

Cofiwch y cyrff gwaedlyd oedd

yn pobi yn yr haul,

yn pydru yn y glaw.

Cofiwch:

Ar ôl yr ornest, aeth yr uchelwyr dewr a glân

i ffwrdd dros y ffin i gael bisged a phaned o de

efo'r Brenin yn Llundain bell.

I chwerthin ac i yfed fel gwr bonheddig da.

Dim ond y Werin oedd ar ôl i deimlo'r poen.

Ond beth wyt ti'n gofio?

Unwaith, mi eisteddes i ar y bryn ger y draffordd,

yn edrych ac yn aros i weld rhyfeddod.

Mi ddaeth y ferch hardda yn y byd

ar hyd i'r draffordd mewn M.G. gwyn.

A phan redes i ar ei hôl i ofyn ei henw,

doeddwn i ddim yn medru ei dal hi.

Mi yrrodd hi dros y ffin i Loegr draw, heb edrych yn ôl.

Mi benlinies i yn drist yn y mwg a'r baw,

heb anadl yn 'yn nghorff

Heb obaith.

Gwag.

Ond beth wyt ti'n gofio?

Unwaith, mi ddes i o hyd i ddyn siaradus

oedd eisiau gweithio dros y ffin.

"Os fyddwch chi'n pleidleisio i mi", meddai'r dyn,

"Mi fydd rhyfeddodau'n rhad,

a gwyrthiau am ddim."

Roedd o'n sefyll y tu allan i'r ganolfan siopa newydd,

Aur ac Arian a siwt Saville Row.

A mi roiodd o bamffledi i bawb oedd yn mynd heibio.

Mi edryches i ar y pamffled.

Roedd arno eiriau tlws a hudol.

Geiriau am "Strength".

Geiriau am "Peace".

Geiriau am "Jobs".

Rhyfeddodau'n wir yn y byd rhwng y ffin a'r môr.

Wedyn, mi weles i ddyn distaw efo arwydd bach,

yn protestio'r byd newydd.

Ac ar yr arwydd oedd pump gair unig:

"Cymru fydd fel Cymru fu"

Ond pwy sy'n cofio rwan?

Sion ab Idris

Images While Thinking About The Border

A flame came across the boarder to change our world.

What do you remember?

horns and hooves?

conquerors and castles?

laws and chains?

Remember the expensive glory?

Remember the bloody bodies that were

baking in the sun,

rotting in the rain.

Remember:

After the contest, the brave, bright nobles went

away over the border to have tea and biscuits

with the King in far away London.

To laugh and to drink like good gentlemen.

Only the common folk were left to feel the pain.

But what do you remember?

Once I sat on a hill near the highway,

looking and waiting to see a wonder.

The most beautiful girl in the world

came along along the highway in a white M.G.

And when I ran after her to ask her name,

I wasn't able to catch her.

She drove over the border to yonder England,

without looking back.

I kneeled sadly in the smoke and mire,

without breathe in my body.

Without hope.

Empty.

But what do you remember?

Once I came across a talkative man,

who wanted to work over the border.

"If you vote for me", said the man,

"Wonders will be cheap, and miracles free."

He was standing outside the new shopping mall,

Gold and Silver and Saville Row suit.

And he gave pamphlets to everyone who was going by.

I looked at the pamphlet.

On it were beautiful and charming words.

Words about "Strength".

Words about "Peace".

Words about "Jobs".

Wonders indeed in the world between the border and the sea.

Then I saw a silent man with a little sign,

protesting the new world.

And on the sign were five lonely words:

"Wales will be as Wales was".

But who remembers now?

John Otley

Cyfieithiad gan / Translation by John Otley

- Details

- Written by: John Otley

- Category: Cymdeithas Madog Chair Competition

- Hits: 2028

Y gerdd fuddugol yn nghystadleuaeth Gadair Cymdeithas Madog, Cwrs Cymraeg Bro Boston, 1989 gan Gwr Y Gogledd (John Otley)

Breuddwydio / Dreaming

Rôn i'n syllu yn flinedig ar y cysgodion

oedd yn dawnsio fel "ballerinas" llwyd

ar lwyfan fy nenfwd brwnt.

Roedd glesni anial yn goleuo'r stafell o'r stryd islaw,

yn hollti'r tywyllwch poeth llaith

oedd yn gafael ynof yn ei grafangau llym.

Ar y briffordd bell, roedd cerddorfa

o gyrn ceir yn canu galargân.

A dyma fi'n gorwedd ar fy ngwely,

heb gysgu, heb ddihuno.

Yno, mi wywodd y cyngerdd aflafar.

Dim gair, dim sibrwd, dim swn.

Y nos heb lais.

Roedd niwl oer gwlyb yn cropian drwy'r ffenest fel cath,

yn llenwi'r stafell fel dwr mewn potel.

Ac yn y tawelwch poenus, mi weles i fyd llwyd,

haearn a rhwd, dur a lludw, maen a baw,

ac adeiladau anhygoel oedd yn herio'r nefoedd.

Mi weles i law brown budr yn syrthio o gymylau fel llech.

A lle roedd y dwr yn llifo,

mi fyddai'r concrit yn toddi fel menyn.

Roedd pobl llwyd yn gwibio heibio

fel gloynnau byw di-liw ar frys gwyllt,

yn cerdded mewn preiddiau o le i le

Roedd eu hwynebau fel maen, yn galed ac yn oer,

heb angerdd, heb bwrpas.

Roedd pawb yn dilyn.

Doedd neb yn arwain.

Mi gerddon nhw heibio i'r gwely

yn ceisio osgoi llygaid yr eneth fach

oedd yn gwerthu glas y gors ger y wardrÙb.

Stopion nhw ddim i edrych ar y rhyfeddod blodeuog,

estron lliwgar yn y byd llwyd.

A phan basion nhw, mi droion nhw ei stondin drosodd

heb feddwl, heb ofal.

Mi adawon nhw'r eneth yn sefyll ar ei phen ei hen

ynghanol adfeilion ei bywyd,

dagrau hallt yn disgleirio fel rhuddemau

yn ngolau gwan yr haul coch.

Yna, mi glywes i swn rhyfedd, cras.

Roedd rhywun yn chwerthin yn walltgo

fel rhyw fath of ffwl.

Ac mi sylweddolies yn sydyn mai fi oedd y ffwl 'na.

Mi eisteddes i i fyny ar fy ngwely,

chwys oer yn llifo o'm hwyneb a'm cefn,

'nghalon yn curo fel tabwrdd bas.

Ond roedd yr heulwen felen groesawgar

yn estyn ei bysedd cynnes drwy'r ffenest,

a roedd robin goch yn dathlu'r dydd newydd

o goeden afalau gyfeillgar.

Mi gysures i fy hun wrth feddwl

mai dim on hunllef oedd hi.

On'd oedd hi?

Gwr Y Gogledd

Dreaming

I was tiredly staring at the shadows

that were dancing like grey ballerinas

on my dirty ceiling stage.

A desolate blueness lit the room from the street below,

splitting the warm damp darkness

that gripped me in its sharp claws.

On the distant highway, an orchestra

of car horns was playing a dirge.

And there I lay on my bed,

not sleeping, not waking.

Then the cachophonic concert faded.

No word, no whisper, no sound.

The night without voice.

A cold wet fog was creeping through the window like a cat,

filling the room like water in a bottle.

And in the painful silence, I saw a grey world,

iron and rust, steel and ash, stone and dirt,

and incredible buildings that were challenging the heavens.

I saw a dirty brown rain falling from clouds like slate.

And where the water ran,

concrete would melt like butter.

Grey people flitted past

like colourless butterflies at a mad dash,

walking in flocks from place to place.

Their faces were like stone, hard and cold,

without passion, without purpose.

Everyone was following.

No-one was leading.

They walked by the bed,

trying to avoid the eyes of the little girl

who was selling forget-me-nots by the wardrobe.

They didn't stop to look at the flowery wonder,

a colourful stranger in the grey world.

And when they passed, they turned her stand over

without thinking, without caring.

They left the girl standing by herself

in the ruins of her life,

salty tears glittering like rubies

in the weak light of the red sun.

Then I heard a strange harsh sound.

Someone was laughing madly

like some sort of fool.

And I suddenly realised that I was that fool.

I sat up in my bed,

cold sweat running from my face and back,

my heart beating like a bass drum.

But the yellow hospitable sunlight

was stretching its warm fingers through the window,

and a robin was celebrating the new day

from a friendly apple tree.

I consoled myself in the thought

that it was only a nightmare.

Wasn't it?

John Otley

Cyfieithiad gan / Translation by Alun Hughes

- Details

- Written by: Graham Hughes

- Category: Cymdeithas Madog Chair Competition

- Hits: 2109

Y darn fuddugol yn nghystadleuaeth Gadair Cymdeithas Madog, Cwrs Cymraeg Bro Ohio, 1990 gan Graham Hughes

Gwreiddiau

Ym mha le y ddylwn i chwilio am fy ngwreiddiau?

Ces i fy ngeni mewn tref ddiwydiannol yn Ne Cymru, lle r'oedd y Cymraeg yn edwino a bron yn diflannu pan oeddwn i'n blentyn. Aferai fy nhad siarad Gwenhwyseg, tafodiaith swynol y cymoedd, ond ni siaradai fy mam dim gair o'r iaith, er iddi ddod o deulu yn llwyr Cymreig, a' thad hi wedi sylfaenu capel Cymraeg yn y dref. (Calfaria, capel y Bedyddwy - rwy'n ei gofio yn finiog dros y blynyddoeth).

Ond, yn y trychineb ofnadwy a ddioddefodd yr iaith, yn y ganrif hon, magwyd fy mam gan fy nhadcu a'm mamgu yn uniaith Saesneg. Byddai'r Gymraeg, yn eu barn nhw, yn rwystredigaeth i lwyddiant yn y byd cyfoes. Efallai eu bod nhw'n iawn.

Wel, dyma fi yn esiampl o'u rhagweliad nhw. Mynd i brifysgol enwog yn Lloegr, mynd yn fargyfreithiwr yn Llundain, yn athro y gyfraith mewn prifysgol enwog yn America. Ysgrifennu llyfrau yn Saesneg; dadlau yn llysgoedd uchaf Lloegr ac American yn Saesneg. Dyna gamp! Llwyddiant ni ellid ei dyfalu gan fy nhadcu a'm mamgu. Llwyddiant dros ben!

Ond dyma beth od! Ar unwaith ar ôl i mi ymadael â Chymru, yn syth dechreuais i deimlo rhyw chwithdod yn y gwythiennau. Hiraethai fy ysbryd am yr hen ddyddiau gynt, a cheisio i neidio dros y cenhedlaethau i gysylltu â fy nghyndeidiau oedd yn byw heb dorri gair o Saesneg. Bu gorfod i mi gychwyn ar y daith hir a brwydro i grafangu yn ôl darn o'm hetifeddiaeth a aeth ar goll. Trwy'r flynyddoedd, yn boenus o araf, rwy wedi ail-gipio ynys fechan o'r filltir sgwar lle trigai'r Cymry.

Ond paham? Peth hawdd ydy colli iaith, ond pa mor hir a chaled yw'r llwybr i'w ail-ennill. Ond fyddai'n haws i gefnu ar yr hen wlad a'r hen iaith a chymodi a'r realiti cyfoes? Ar ôl gyrfa ar uchelgais yn anelu yn unig at lwyddiant ym myd eang y diwylliant Saesneg, "beth yw'r ots gennyf i am Gymru?"

Ond mae'r gwreiddiau yn gadarn, ond ydynt? Mae llawenydd a dagrau y profiad Cymreig trwy'r oesau yn dal i bwyso arnaf a fyddan nhw ddim yn fy ngadael i'n llonydd. D'ydi hyn ddim yn reswm i ofidio. Mae'r heniaith yn rhoi arial i'm calon ac, fel y dywed y bard:

"Nol blino treiglo pob tref

Teg edrych tuag adref."

Ie, wir, peth cadarn ydi gwreiddiau.

Graham Hughes

Roots

I was born in an industrial town in South Wales where the Welsh language was in a state of decay, on the verge of disappearing, even when I was a child. My father spoke Gwenhwysig, that charming dialect of the valleys, but my mother could not speak a word of the old language, even though she came from a completely Welsh family, and her father had founded a Welsh language chapel in the town. (It was a Baptist chapel, Calfaria, and I remember it so sharply after all these years).

But, in that terrible disaster that overwhelmed the language in this century, my grandparents brought up my mother to be monoglot English. They thought that Welsh would be an impediment to success in the modern world. Perhaps they were right.

I am certainly an example of their foresight. I went to a famous English university, became a barrister in London and a professor of law in a well known American university. I wrote books in English and argued in English in the highest courts in England and America. What a success story! Acheivements that my grandparents could not have dreamed of. Tremendous success!

But something peculiar happened. Once I had left Wales, suddenly I could feel a current of uneasiness in my veins. My spirit seemed to yearn for bygone days; it sought to leap over generations and link up with my ancestors who had lived without ever speaking a word of English. I felt compelled to set out on a long journey, to struggle to wrest back some piece of my lost inheritance. And over the years, in a painfully slow way, I have managed to retake possession of a small strip of that square mile where the Welsh once lived.

But why? It's so easy to lose a language and the path to regaining it is so long and hard. Wouldn't it be easier to turn one's back on the old country and the old language and come to terms with contemporary reality? When all my ambition and my carerr had been directed at success int he broad world of English culture, "what should Wales matter to me?"

But roots are so powerful, aren't they? The joy and the tears of the Welsh experience through the ages are always in my mind; they won't let me forget. But that's not something to regret. The old language thrills me, and, as the poet wrote:

"After wandering through so many lands,

It is sweet to look towards home."

Yes, roots are powerful things, indeed.

Graham Hughes

Cyfieithiad gan / Translation by Graham Hughes